Gaston Hélie

Listed on the AKOUN

Autodidactic painter Gaston Hélie attended drawing and sculpting classes at the School of Fine Arts in his home town of Caen. A painting enthusiast since the age of 17, and strengthened by his long experience of exhibiting in regional and national shows (including the Salon des artistes français and the Salon National des Beaux Arts in Paris), this artist has over the course of his unique creative path won numerous awards, which have contributed to establishing his renown.

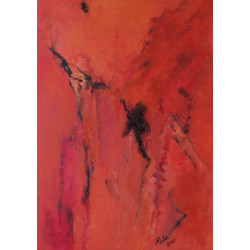

Over the course of his long artistic career, Gaston Hélie has always been driven by a desire for renewal, leading him towards increasing freedom both in the interpretation of his landscapes (a favourite theme in his work) and in his pictorial technique. The landscapes he presents are not painted on site, but are directly drawn from his memory. They are reinvented poetic visions that express reminiscences tinged with the painter’s emotions. His style has become increasingly stark and uncluttered over the years, conveying the subject’s spirituality far beyond its simple formal aspect. In Gaston Hélie’s work, which is somewhere between figuration and abstraction, references to nature have grown more and more tenuous, and the artist has little by little led us from the material to the immaterial, from the natural world to the metaphysical world, from the tangible universe to the spiritual universe.

If Gaston Hélie’s approach is not to rethink art, then his reflection on what it should express is profound and extremely interesting. Nourished by Aristotle’s philosophical thought that, “the function of art is not to represent the visible, but to render visible,” and by the idea dear to Jean Bazaine that, through their work, artists express the depths of their soul, the artist claims, “If I began painting, it was to better discover myself.” Less drawn to Renaissance art, which places emphasis on idealised formal beauty, Gaston Hélie appreciates gothic art (particularly its sculpture), underlining its power of expression, and this is hardly surprising when we remember the extent to which this art was representative of medieval beliefs in a tangible world where everything was merely a symbol of an invisible spiritual world. Yet it is the great pictorial breakthroughs of the 20th century that forged his artistic convictions: the Cézanne revolution and Georges Braque’s cubism in terms of formal treatment, Wassily Kandinsky’s art in terms of its quest for spirituality, Roger Bissière’s intimate and poetic work that evolved towards non-figuration in the post-war years, Nicolas de Staël’s painting that was both figurative and abstract, Olivier Debré’s Lyrical Abstraction that “materialised” emotions, and Mark Rothko’s Abstract Expressionism that expressed feelings. Gaston Hélie’s admiration for these artists only increased his determination to develop a personal style by way of constant exploration, attentive to both the outer world and to the “inner need of the soul” advocated by Wassily Kandinsky.

The artist’s subjectivity is consequently perfectly placed to reproduce the unique essence of evanescent landscapes. The subtle play of pictorial elements unearths the buried part of a tangible world that he wants to help us explore. Gaston Hélie manages to perfectly distance himself from nature thanks to a pictorial medium that sculpts volumes by juxtaposing interweaving shapes, flouting laws of perspective. He loves deconstructing shapes through skilful use of geometry. His compositions’ energy lies as much in the positioning and strength of line as in the arrangement of volumes of colour and adept distribution of light and shadow effects. Attentive to the harmony of colours, as of 1985 the artist abandoned the bright blends of his early years in favour of a lighter palette of vibrant, monochrome colours, and gradually replaced the knife with the brush for more subtle flowing effects. Since 2007, his starkness has become absolute and his landscapes metaphorical. Much like Mark Rothko, whose famous iconic landscapes are marked by horizontal lines and the play of strips of colour, Gaston Hélie conveys his vision of the tangible world in superb wavy compositions, hugging like a pearl in a jewel case the very heart of the subject that stirs the artist’s soul.

This renewed vision transposes into painting the musical and poetic harmony that the painter has always subconsciously sought yet attained at a relatively late date. In the 1990s, he understood that what he was looking for was “a sort of musicality in painting,” and managed to analyse the way in which music was composed in order to transpose its rules into his pictorial art. “Verticality is stability. Only curves, spirals and reverse curves suggest movement,” he explains. Yet even if, for him, painting “should be listened to like a sonata or a quartet which he joins in an artistic expression beyond commonplace words and images,” the artist goes further in his approach and does not content himself with transposing mere rhythm into his pieces. Following the example of Friedrich Nietzsche, for whom music expressed “what is metaphysical in the physical world” and was therefore considered the artform that best touches the human soul, Gaston Hélie proves he is capable of expressing his inner spiritual world in painting and of communicating it to the observer. It was this quest for empathy that ultimately and inescapably became central for him, and it finds its best expression in his 2014 series Variation.

“Painters do nothing but paint themselves” by releasing their emotional vibrations onto the essence of the world that they transcend. Gaston Hélie succeeds this masterfully in a sort of rediscovered inner peace. Yet his quest is by no means over, because painters never know how far they can go. Strength of line and tone colour remain the keywords for this extraordinary artist as he continues to create spiritual paintings and to “Make music in painting”.

Over the course of his long artistic career, Gaston Hélie has always been driven by a desire for renewal, leading him towards increasing freedom both in the interpretation of his landscapes (a favourite theme in his work) and in his pictorial technique. The landscapes he presents are not painted on site, but are directly drawn from his memory. They are reinvented poetic visions that express reminiscences tinged with the painter’s emotions. His style has become increasingly stark and uncluttered over the years, conveying the subject’s spirituality far beyond its simple formal aspect. In Gaston Hélie’s work, which is somewhere between figuration and abstraction, references to nature have grown more and more tenuous, and the artist has little by little led us from the material to the immaterial, from the natural world to the metaphysical world, from the tangible universe to the spiritual universe.

If Gaston Hélie’s approach is not to rethink art, then his reflection on what it should express is profound and extremely interesting. Nourished by Aristotle’s philosophical thought that, “the function of art is not to represent the visible, but to render visible,” and by the idea dear to Jean Bazaine that, through their work, artists express the depths of their soul, the artist claims, “If I began painting, it was to better discover myself.” Less drawn to Renaissance art, which places emphasis on idealised formal beauty, Gaston Hélie appreciates gothic art (particularly its sculpture), underlining its power of expression, and this is hardly surprising when we remember the extent to which this art was representative of medieval beliefs in a tangible world where everything was merely a symbol of an invisible spiritual world. Yet it is the great pictorial breakthroughs of the 20th century that forged his artistic convictions: the Cézanne revolution and Georges Braque’s cubism in terms of formal treatment, Wassily Kandinsky’s art in terms of its quest for spirituality, Roger Bissière’s intimate and poetic work that evolved towards non-figuration in the post-war years, Nicolas de Staël’s painting that was both figurative and abstract, Olivier Debré’s Lyrical Abstraction that “materialised” emotions, and Mark Rothko’s Abstract Expressionism that expressed feelings. Gaston Hélie’s admiration for these artists only increased his determination to develop a personal style by way of constant exploration, attentive to both the outer world and to the “inner need of the soul” advocated by Wassily Kandinsky.

The artist’s subjectivity is consequently perfectly placed to reproduce the unique essence of evanescent landscapes. The subtle play of pictorial elements unearths the buried part of a tangible world that he wants to help us explore. Gaston Hélie manages to perfectly distance himself from nature thanks to a pictorial medium that sculpts volumes by juxtaposing interweaving shapes, flouting laws of perspective. He loves deconstructing shapes through skilful use of geometry. His compositions’ energy lies as much in the positioning and strength of line as in the arrangement of volumes of colour and adept distribution of light and shadow effects. Attentive to the harmony of colours, as of 1985 the artist abandoned the bright blends of his early years in favour of a lighter palette of vibrant, monochrome colours, and gradually replaced the knife with the brush for more subtle flowing effects. Since 2007, his starkness has become absolute and his landscapes metaphorical. Much like Mark Rothko, whose famous iconic landscapes are marked by horizontal lines and the play of strips of colour, Gaston Hélie conveys his vision of the tangible world in superb wavy compositions, hugging like a pearl in a jewel case the very heart of the subject that stirs the artist’s soul.

This renewed vision transposes into painting the musical and poetic harmony that the painter has always subconsciously sought yet attained at a relatively late date. In the 1990s, he understood that what he was looking for was “a sort of musicality in painting,” and managed to analyse the way in which music was composed in order to transpose its rules into his pictorial art. “Verticality is stability. Only curves, spirals and reverse curves suggest movement,” he explains. Yet even if, for him, painting “should be listened to like a sonata or a quartet which he joins in an artistic expression beyond commonplace words and images,” the artist goes further in his approach and does not content himself with transposing mere rhythm into his pieces. Following the example of Friedrich Nietzsche, for whom music expressed “what is metaphysical in the physical world” and was therefore considered the artform that best touches the human soul, Gaston Hélie proves he is capable of expressing his inner spiritual world in painting and of communicating it to the observer. It was this quest for empathy that ultimately and inescapably became central for him, and it finds its best expression in his 2014 series Variation.

“Painters do nothing but paint themselves” by releasing their emotional vibrations onto the essence of the world that they transcend. Gaston Hélie succeeds this masterfully in a sort of rediscovered inner peace. Yet his quest is by no means over, because painters never know how far they can go. Strength of line and tone colour remain the keywords for this extraordinary artist as he continues to create spiritual paintings and to “Make music in painting”.

Francine Bunel-Malras, Art Historian